by Marco Biraghi

Like other celebrities – though these are more usually found in the world of entertainment than in architectural history – a remarkable reputation has accrued to Manfredo Tafuri, furthering the spread of his name and his books; but it has also distorted his message, encouraging the miscomprehension of his thought. (It must be admitted that Tafuri, with his occasionally wilful unintelligibility, was complicit in this himself). In these warped interpretations, Tafuri’s ideas have been read as a diagnosis of an apocalyptic ‘end of architecture’, or at least as an irrationally pessimistic stance against the discipline. But in fact his entire biography shows that, behind the mask of the provocateur, Tafuri intended the construction of a serious critical consciousness and a role for the architectural historian within it.

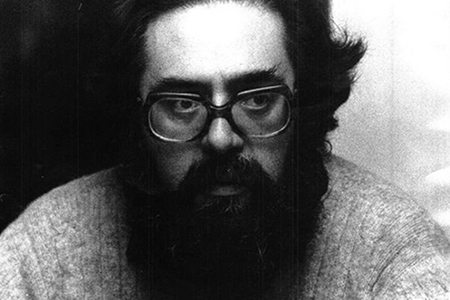

Manfredo Tafuri was born in Rome in 1935, and he graduated from the Faculty of Architecture of the University of Rome in July 1960. As a student he joined protests against the backwardness and poor teaching of his professors, participating in the first occupations of Italian universities. In the midst of this political activity he presented a thesis on the history of architecture – concerning the buildings of the Hohenstaufen monarchy in Sicily – rather than the required architectural project: a polemical gesture against the elderly academics who made up the degree committee, and who had been involved with the Fascist regime.

From the early sixties on Tafuri focused his studies on the history of art and architecture (his teacher was art historian Giulio Carlo Argan, who later became the first communist mayor of Rome). He was also deeply involved in architectural culture outside the academy, contributing polemical articles on the urban situation of Rome to Casabella-Continuità, edited by Ernesto Nathan Rogers. In 1964 he published his first book, Ludovico Quaroni and the Development of Italian Architectural Culture. It’s a sort of interview with Quaroni – Tafuri was his teaching assistant at the time – in which Tafuri’s words often sound like paraphrases of Quaroni’s. For him Quaroni was the master of doubt, a model of the critical and self-critical architect who taught him the concept and the praxis of contradiction.

In 1968 Tafuri published his canonical book Theories and History of Architecture. In the same year – after a short period of teaching at the Faculty of Architecture in Milan, where he replaced an ailing Ernesto Rogers, and another period at the University of Palermo – he won the chair of history of architecture at the IUAV in Venice. He remained there for the rest of his life as director of the Institute (then Department) of History of Architecture, eventually becoming synonymously entwined with the city as leader of the so-called Venice School of architectural history. In those years he also began to read the unorthodox Marxist writings of Walter Benjamin, and he met the young philosopher and future leftist politician Massimo Cacciari. Both were to be crucial influences on the formation of Tafuri’s conception of history. Reflecting these two encounters, the topic that unites all the chapters of Theories and History is that of crisis: crisis of the architectural object, of the subject-architect, of ideology, of history, of critique, and of language.

His next book, Architecture and Utopia, is closely related to Theories and History. Retracing the development of architecture from the late eighteenth century to the beginning of the seventies, he concludes by discounting any possibility of utopia for the architecture of the era of late capitalism. This is what Tafuri sees as ‘the “drama” of architecture, today: i.e. the problem of being obliged to go back to being pure architecture, a question of form without utopia, sublime uselessness, in the best of cases’. As he was to say in an interview with Richard Ingersoll, ten years later: ‘There are no more utopias, the architecture of commitment, which tried to engage us politically and socially, is finished, and what is left to pursue is empty architecture. […] I really don’t see this as the “failure of Modern architecture”; we must look instead at what an architect could do when certain things were not possible, and what he could do when they were possible’.

For Tafuri, architecture’s loss of the chance to be utopian is not a judgement, it’s the result of a historical process. Utopia – and ideology, as its foundational assumption – go into crisis when they are realised. The Sphere and the Labyrinth, published in 1980, starts with this assumption: ‘It is useless to cry over a given: ideology has mutated into reality; even if the romantic dream of the intellectuals who offered to guide the destiny of the productive realm remains, logically, in the superstructure of utopia’. It was precisely for this reason that Tafuri condemned the neo-avant-gardes of the sixties and seventies, Archigram and Superstudio among them, for being guilty of believing in that ‘romantic dream’. But for him the problem was more general: the whole of Modernity – and most of all, Late Modernity – is a time in which not only utopia and reality but every pair of opposites, every contradiction, cannot coexist. Unlike the Renaissance, Modernity is an era in which contradictions produce a mere sum of pluralities, of dissimilar multiplicities, within which each constantly aspires to prevail over the other, to assert itself – a war of all against all. Only humanistic Renaissance culture embraced contradiction as an essential form of culture and therefore – more generally – of reality itself.

This was why, after 1980,Tafuri returned to his long broken-off studies of the Renaissance, which he had begun during the sixties (for example in his book The Architecture of Humanism). In his final book, Interpreting the Renaissance (published in 1992, two years before his death), Tafuri wrote: ‘Architecture and culture of the humanist period attempt to keep the two opposing poles solidly united: one pole is based on stable foundations, while the other relates to subjective will. […], it is a matter of a complexio oppositorum, a culture of contradiction’.

Dedicating himself to a return to the Renaissance in the last years of his life did not mean a retreat from the contemporary situation, a sign of ‘boredom’ or ‘irritation’, or a radical break with his career up to this point (as is often claimed); it meant instead a sincere investigation of – and a personal quest for – the complexio (plot, or intertwinement) of contradictions that belong to reality as such. If the historical project does not consist of unveiling a grand truth, but rather lies in shedding light upon a ‘constellation of events’ or ‘nodes in which events, times, and mentalities intersect,’ the historian’s task is to keep these nodes in tension among themselves rather than producing a false totality that smoothes over the cracks. So, for example, if the node of the Renaissance is in a productive, significant tension with the node of philology, the latter is also in tension with the node of the critique of ideology, which is in turn in tension with the node of contemporaneity. And both epochs are in a productive, albeit different, tension with the nodes of utopia and reality. On this history constructed from tensions and contradictions Manfredo Tafuri worked his entire life.

Published on «The Architectural Review», 9 June 2014

june 14, 2014