by Simon Sadler

10 January 2011

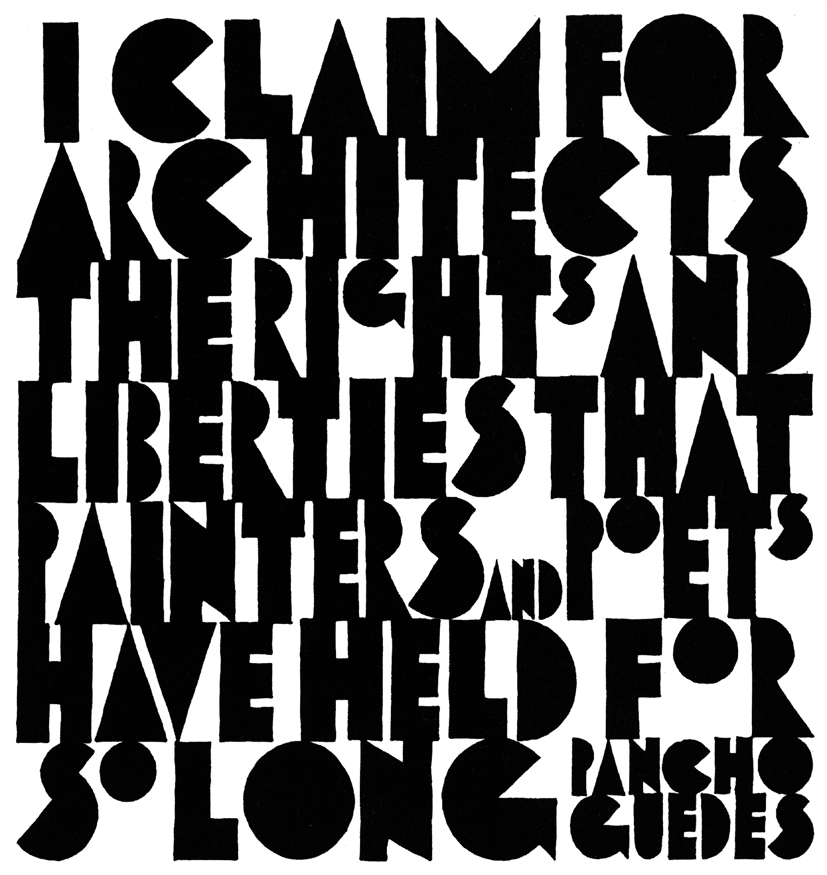

Forty-six years after the «Architectural Review» noted that Mozambique’s Pancho Guedes had received «no attention … by the outside world,» [1] little has changed, and yet Guedes’ work maps back onto a larger history of modern architecture in at least three obvious and interrelated ways. The first is as a reminder of an expressionist, organicist tendency that re-emerged in the 1950s and 1960s as modernism’s road less travelled. A second way is as part of a move toward the programmatic revision of modernism hatched around Team 10’s discussions of the 1950s-70s. A third way is in relation to the question of what postcolonial modernism was thought to constitute, as modernism developed outside of its European and North American base. This essay will consider Guedes’ place on this map of post-war modernism, but it must also allow that Guedes is in some ways off that map, and that the map may be a fiction: is there one modernism to map, with one history, for one world? Is there, for that matter, one Guedes?

Let us return to 1961, the year the «Architectural Review» told its readers about Guedes, and three years after Guedes completed what can serve here as his signature building, the so-called Smiling Lion apartment block of 1956-1958 in Lourenço Marques (now Maputo), Mozambique. With this building, Guedes took advantage as the building’s developer to give full rein to a personal style he would call the “Stiloguedes”, the “Guedes Style” [2]. The building was childlike in its exuberance, part-inspired by a drawing given to the architect by his six-year-old son [3], drooping balconies with slightly elliptical sides seeming to rock within the block’s amorphous, sculpted sides, crowned with boldly patterned parapets and thin-shell vaults, the ensemble finished with paintings and martial sculptural motifs. It is also in 1961 that the leading historian and critic Nikolaus Pevsner renews his campaign against this sort of “neo-Art Nouveau” stemming from Antonio Gaudì [4]. For Pevsner, design was a moral commitment confirmed in the revolutionary puritanism of the Bauhaus.

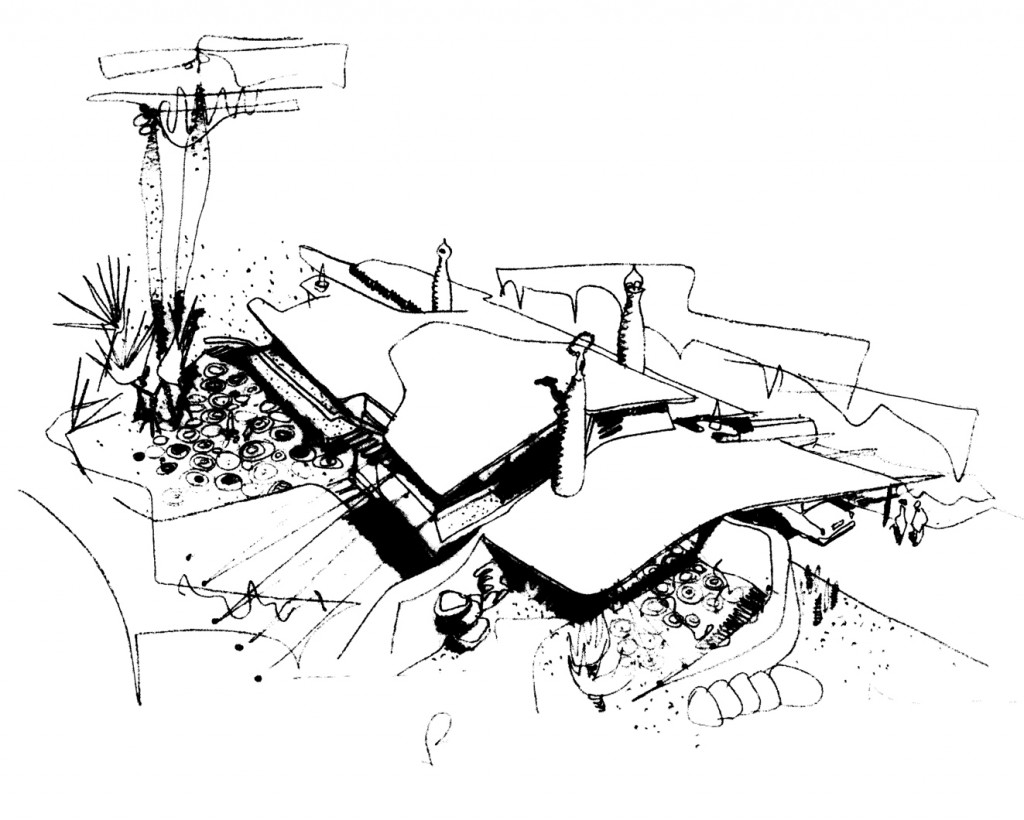

At stake was modernism’s unitary map and character. As one reviewer of Pevsner’s writing noted at the time, in the work of Guedes, and more prominently that of Eero Saarinen, Pevsner perceived a near and present danger to the International Style [5]. Moreover there was something peculiarly unstable in the work of Guedes, even compared to Saarinen—a desire to express not so much some ‘outward’ experience (such as the sensation of flight famously depicted by Saarinen’s 1956-62 TWA air terminal at Idlewild), but rather an “outsider” ‘condition’, like that pursued in ‘art autre’ in France and by the unruly architecture of Bruce Goff in Oklahoma. Guedes’ work also hailed some “inward” state similar to that which was then coalescing around situationism. «Architecture is not apprehended as intellectual experience but as sensation—an emotion», Guedes announced in his dissertation. «Buildings must become presences—be like vast apocalyptic monsters or gently floating albatrosses … so invented as to be remembered forever like the temples of India and the pyramids of Egypt … I have asked nature to invade architecture exuberantly as if it were a ruin.» [6]

Guedes was recognized as part of a dissident movement in architecture, often likened to the Angry Young Men of 1950s literature [7], invigorated by the gradual rediscovery of the pioneering early-twentieth-century art nouveau, expressionist, futurist and surrealist avant-gardes [8]. In his colourful graphics and bulbous, cosseting spaces there was a striking family resemblance between Guedes and the new avant-gardes of the 1960s like Archigram, all of which were attracting Pevsner’s consternation [9]. Pevsner, though, was increasingly countered by a new generation of critic-historians, such as his student Reyner Banham, who entertained Guedes in the hallowed pub of the «Architectural Review»’s office basement [10].

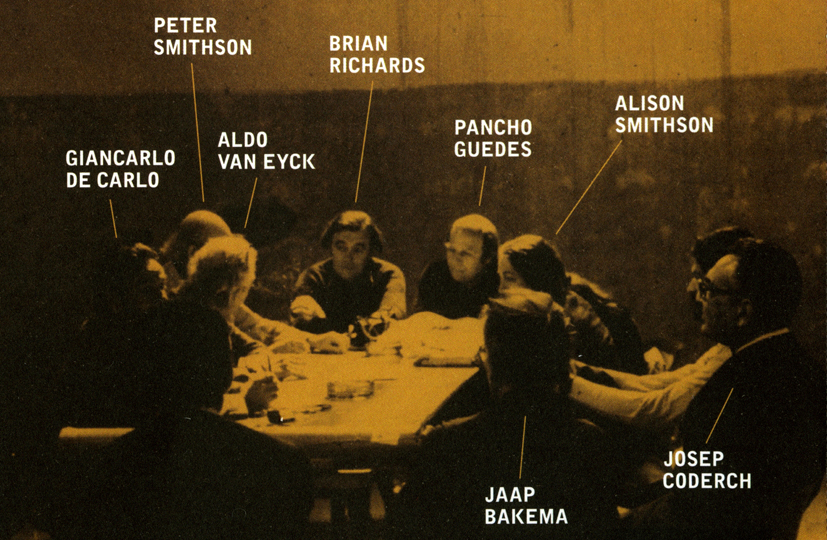

Like Banham, Guedes was also maintaining conversations with Team 10, led by more sober figures such as Alison and Peter Smithson—so-called Brutalist architects for whom the ultra-experimental, dadaist-surrealist-expressionist tendency epitomized by Archigram appeared as a troublesome offspring [11]. Some of Guedes’ designs, like that for the Nurses Training College at Lourenço Marques (1964-65), bore a distinct Brutalist impress. Guedes attended Team 10 meetings from 1962 to 1976, and in lieu of a final Team 10 meeting planned for Portugal in 1981 the Smithsons visited Guedes in Lisbon [12]. If Archigram-style architects cultivated renegade roles, Team 10 architects aspired to a direct succession from the first central organizing body of modern architecture, CIAM, styling itself as a “family” and “discussion group” rather than an “avant-garde”. Team 10 aimed to save the modern movement from its seemingly imminent fragmentation by talking through practitioners’ common concerns within post-war architecture’s expanded field. Broadly, Team 10 was troubled that a single, ‘Hegelian’ convergence of design into a universal modern movement paid inadequate attention to the ways in which architecture was having to address regionalism, anthropology, urban and economic growth. For Guedes, these concerns were as compelling as his need to vent empathies with the avant-garde.

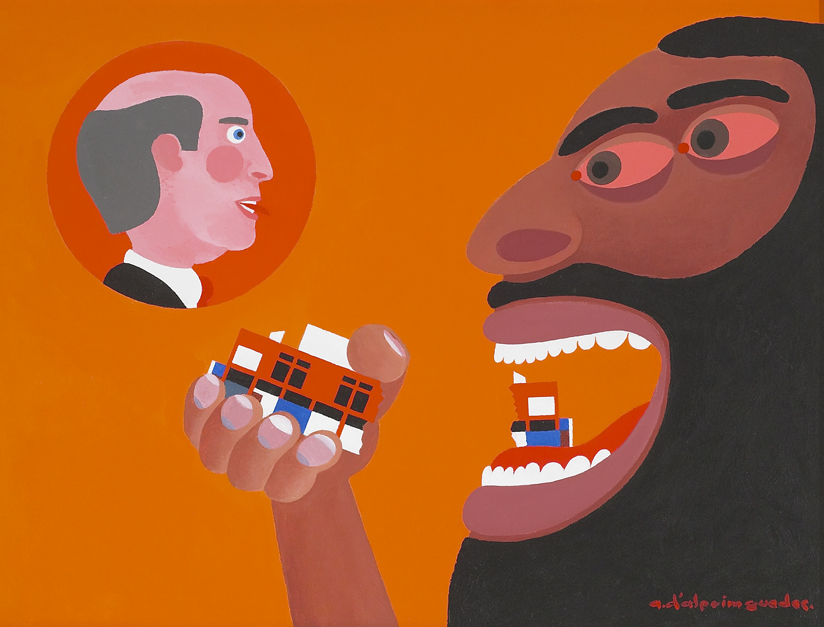

Guedes apparently managed these multiple interests through his manifold personae. The adoption of multiple identities was not simply a surrealist or dadaist (let alone postmodern) strategy; some journalists at the «Architectural Review» used ‘nom des plumes’ or wrote in different registers for different circumstances—even the level-headed Pevsner delegated his research into nineteenth-century vernacular architecture to the fictive ‘Peter F. R. Donner’ [13]. Guedes clarified his various monikers: «Amâncio Guedes is the spirit of Pancho Guedes, first revealed internationally in the pages of the “Architectural Review”. It was discovered by Banham who descended with him to the bar basement at Queen Anne’s Gate in 1960». «Pancho Guedes,» in turn, «is the father, the inventor of all the art works,» while «A. d’Alpoim Guedes is the son.» [14] Guedes created this trinity to conceive, execute, and archive a body of work that had emerged out of multipart influences, concerns, movements and geographies. Similarly Le Corbusier, the invented identity of Charles-Edouard Jeanneret, discovered an underlying feminine psyche within himself in the 1930s, and eventually allowed himself an untrammelled range of architectural modes by turns archaic, vaulted, monumental, and raw—here were the styles that could be discerned in the Guedes portfolio too, and which caused Pevsner so much anxiety, and which signalled to Team 10 that modernism was no longer a single methodology.

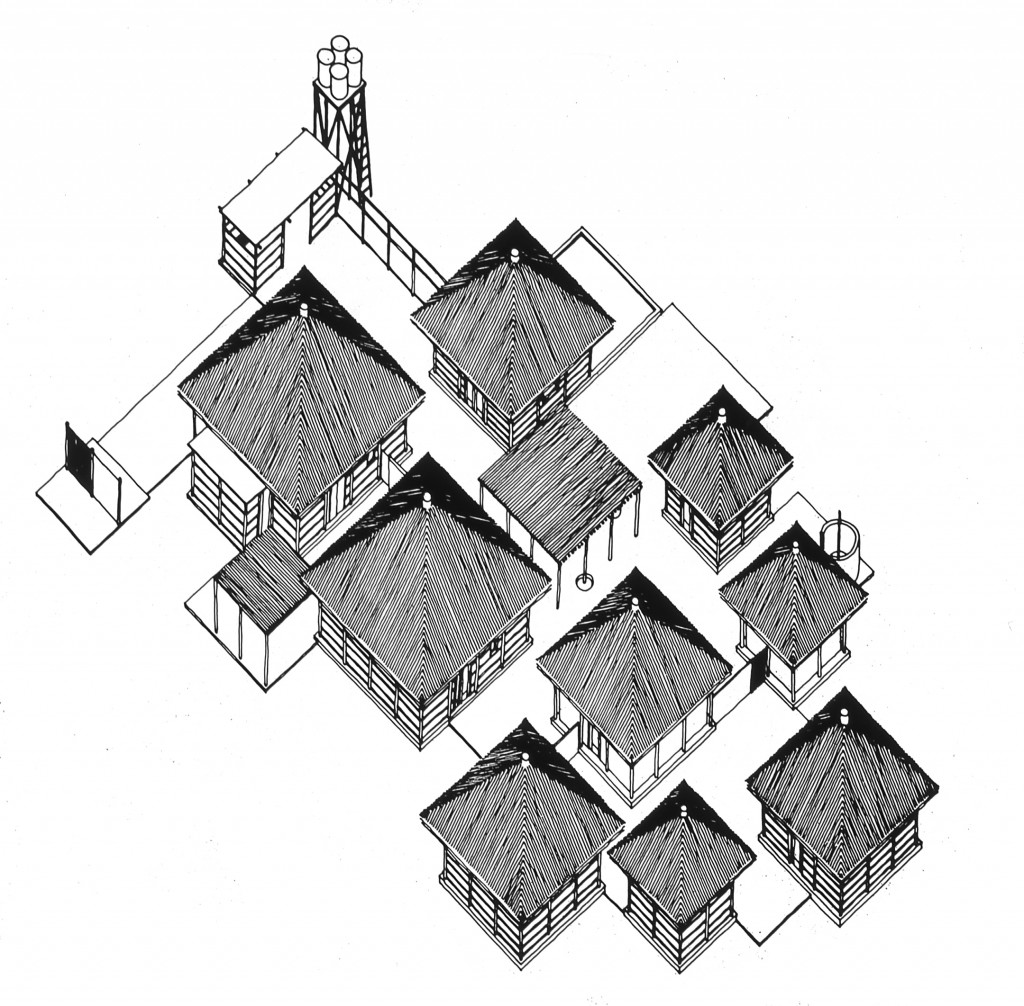

Arguably, though, Guedes’ stylistic dilemma was more complex than that faced either by Archigram or by other members of Team 10, working as he did as an émigré Portuguese in Mozambique. Granted, there were precedents for architecture at once modern yet responsive to climates, cultures and vernaculars not of Western origin. Le Corbusier’s projects in 1950s India were joined by Louis Kahn’s Dhaka in the 1960s. Balkrishna Doshi, reciprocally, was an Indian participant in Team 10 synthesizing the Corbusian idiom with local building traditions. Team 10’s Aldo van Eyck insisted that modern architecture had things to learn from the North African settlement patterns of the Dogon, much as Guedes drew upon the forms (such as curved walls) found in the stone ruins of the Great Zimbabwe and the African kraals [15]. But perhaps the situation most closely approximating that of Guedes was that of Brazilian colleagues. Brazil and Mozambique—one a former colony, the other moving towards independence—retained a heavy Portuguese influence while endeavouring to modernize. Guedes, like a youthful Oscar Niemeyer [16], projected cubist, syncopated conversions of local motifs and patterns. But there was a telling distinction between Guedes in Mozambique and postcolonial identity-building happening elsewhere. Guedes was without the commissions—and encumbrances—of central and state patronage, and primarily accepted private, middle-class house designs as his laboratory. Other than these, «in Mozambique, I worked mostly for missionaries and banks and big foreign companies», Guedes admits. Describing it as though it were the Foucauldian colonial heterotopia [17], Guedes continues: «Lourenço Marques was a fiction. It wasn’t Portuguese. Lourenço Marques was always the Transvaal port for imports and exports and it was the people, the foreigners involved in the ports that I worked for.» [18]

So the opportunity to monumentalize the democratic, modernizing institutions of the so-called developing world (like parliaments and universities) largely eluded Guedes, even as they were being seized upon by Le Corbusier, Kahn, and the Latin American architects that Guedes admired, like Niemeyer and Juan O’Gorman. While explicitly grounding him in nationhood, Guedes’ 1985 self-analysis ‘Vitruvius Moçambicanus’ was neither an architectural rule book nor the synthesis of a national spirit [19]. Guedes’ outlook was international, inventive, and individualist, making him a witness to several cultures rather than a member of any one. He moved between Ancient and Modern, Dada and Team 10, from the medieval streetscape to the street plans of Ildefons Cerdà, from Gaudì to Le Corbusier, from Italy to Portugal to southern Africa. The multiple styles asynchronously presented by the ‘Vitruvius Moçambicanus’ challenge location within any particular time, space, teleology, or even authorship. Curiously, this made Guedes’ Mozambiquean architecture ambivalent toward colonial [20] and local ancestry alike, and he discussed his European ancestry as though a visitor to it, inquisitive about the Renaissance, fascinated by Barcelona, brooding about his Portuguese homeland. In Mozambique, he designed and built some five-hundred buildings, enough, as he puts it, to constitute a small city, before conceding in 1975 the impossibility of riding out the political disturbances there, and slipping across the border to South Africa. There, he worked at the University of the Witwatersrand within the confines of the apartheid system while looking forward to South Africa’s liberation.

To draw on the 1960s postcolonial theory of Frantz Fanon, Guedes’ portfolio had inklings of a postcolonial national consciousness, holding the Eurocentric at bay, but at the cost of a hypostatizing exoticism, lauding idiosyncrasy and little challenging the prevalence of the bourgeoisie, and so remaining tangential to cultural collectivism (Guedes assembled around him a closely-directed atelier of black African draughtsmen, craftsmen and artists) [21]. We might compare Guedes with Egypt’s Hassan Fathy, whose career, if not exemplary, resisted the quasi-colonialism of modernism by rethinking the potential of indigenous forms, plans, crafts and materials. For Guedes, however, indigenous architecture spoke to racial and cultural inequity rather than synthesis: «When buildings were needed but there was almost no money, I always turned to the traditional way of building, to the Mozambican vernacular to make a beginning … Yet it was only as a last recourse that such proposals would be accepted. The blacks [sic] always wanted a ‘casa de branco’—a white man’s house, instead. They were ashamed of their own wonderful, most suitable and economical grass houses.” [22]

Nonetheless—and almost in spite Guedes’ rejection of any teleology—we can posit something modernistic about his work: the defiance of hegemony, be it national, stylistic, or institutional. Here is the freedom allowed to the bourgeois man at the periphery (the license afforded Guedes, working in an environment relatively unencumbered by political intervention bar clients’ wishes and economics, was envied by members of Team 10) [23]. In truth, only the better-known part of the prolific Guedes portfolio is in the ‘Stiloguedes’, and superficially Guedes’ work in downtown Lourenço Marques, while quirky, was not necessarily easy to distinguish on first sight from that of the ‘tropical’ (née ‘colonial’) architecture being exported from European metropolitan centres like London [24]. («The Octavio Lobo Building is a narrow slice of offices, a building for hire, a carcass to be stuffed with business», Guedes commented with disarmingly self-critical insight of a building he designed with the typical ‘tropical architecture’ devices like ‘brises-soleil’.) [25] Yet Guedes kept his distance from the metropolitan ‘networks’ of tropical architecture, and even from Team 10. He likewise preferred the southern edges of Europe to its hubs, places like Gaudì’s Catalonia, and post-war Portugal, where peasant culture remained as powerful as its modernizing industrial nemesis. A little like his Portuguese contemporaries Fernando Tavora and Álvaro Siza, in ethos if less so in style, Guedes’ architecture played its part in international modernism precisely by offering “inflection” to it. Guedes’ work of the 1950s-70s might qualify as an instance of critical regionalism, if of a somewhat flamboyant and monumental stripe that might remind the viewer of that era’s Austrian avant-garde. His architecture countered the shallowness and hastiness often associated with modernization in the developing world, especially in go-go economies like that of post-war Lourenço Marques. Guedes was professionally and emotionally invested in Africa in a way that distinguished him from European intellectuals, like Rimbaud and Gauguin, who earlier tried to ‘lose’ themselves in the colonial world.

Guedes correspondingly represented an optimistic, one-world cultural unity (in the face of centralization and deference), informed perhaps by the 1950s and 1960s rhetoric of the United Nations and pan-Africanism. Transcending the incipient civil strife of Mozambique and South Africa, for instance, Guedes’ charming paintings (which he regarded as inextricable from design) are quilted from a variety of skin colours and reduce humanness neither to social type, nor individual expression, nor political affiliation, instead directing our attention to the visionary, to movement, and to social interaction. An ideogrammatic painting of his Smiling Lion apartment block [26] seemingly ameliorated, into an organic cross section, an otherwise disconcerting racial and class stratification, with servants lodged in the attic (an arrangement that had begun to disappear in Europe after the First World War). The painting typifies Guedes’ preoccupation with an almost Bachelardian sense of dwelling, insisting that a unitary spirit of ‘being’ is common to all humans at all times and in all places, even if architecture itself is unable to rise to it, and even as Guedes’ actual buildings were succumbing to neglect and war.

By both circumstance and choice, Guedes was an awkward fit for a singular history of a singular modernism in a singular world. In his art he defiantly nurtured something of “the natural man in his completely wild and untamed state” which, Hegel argued, excluded (black) Africans and their continent from world history. [27] Pevsner and others wanted to consolidate modernism’s narrative as one of rational public service; Guedes, like other Team 10 participants, preferred to think about modern architecture through sets of familial relations and resemblances. These contrary relations could nevertheless be encompassed by modernism at its most reflexive. «To visualize architecture as a more expansive art,» wrote Julian Beinart in 1961 of Guedes’ circle, «social commitment includes for them also a commitment to those aspirations, irrationalities and phantasies which are a large part of life and an even larger part of art.» [28] This outlook continues to inform the apparent ‘delirium’ nestled in contemporary architecture. Architecture today is also challenged, by globalization, to represent transnational culture in ways somewhat familiar to the architects of the late colonial and postcolonial moment. Misguided or not, coherent or not, architects sometimes grant themselves a certain distance from dictate and cooption. Guedes wrung a cosmopolitanism from the pragmatic practice of commercial architecture, in the pragmatic environment of postwar Lourenço Marques.

[first published: Sadler, Simon. ‘One modernism? One history, One world, One Guedes?’ in: Guedes, Pedro (ed.) Pancho Guedes – Vitruvius Mozambicanus, Lisboa: Museu Colecção Berardo, 2009, pp. 268-275]

[1] Julian Beinart, ‘Amancio Guedes, architect of Laurenço Marques’, «Architectural Review», vol. 129, pp. 240-251, p. 241, April 1961. For a concise bibliography for Guedes, see Timothy Ostler, ‘Guedes, Amancio,’ ‘Grove Art Online’ (accessed 20 August 2007), http://www.groveart.com/shared/views/article.html?section=art.035398.

[2] On ‘Stiloguedes’, see ‘Vitruvius Moçambicanus’, «Arquitectura Portuguesa», vol. 1, no. 2, 1985, pp. 12–62, available at http://www.guedes.info/contfram.htm (accessed 30 August, 2007).

[3] Pedro Guedes also became an architect.

[4] See for instance Nikolaus Pevsner, ‘Modern Architecture and the Historian, or, the Return of Historicism’, «RIBA Journal», April 1961, pp. 230-240, and the revised edition of his respected survey ‘An Outline of European Architecture’.

[5] Clifford Musgrave, ‘Review: A new edition of Pevsner’s European Architecture’, «The Burlington Magazine», vol. 103, no. 704., November 1961, pp. 469-470.

[6] Quoted in Pancho Guedes, ‘Introduction’, http://www.guedes.info/contfram.htm (accessed 30 August 2007).

[7] See for instance Beinart, op. cit.

[8] The rediscovery was affected, for example, through books like Ulrich Conrads and Hans Gunther Sperlich’s ‘Phantastische Architektur’, and Reyner Banham’s ‘Theory and Design in the First Machine Age’, both 1960.

[9] Indeed, Archigram’s Dennis Crompton led the team that produced the ‘Amancio Guedes’ catalogue and exhibition at the Architectural Association in 1980, though for the most part the design and editing of both were done by Pedro Guedes (correspondence with Dennis Crompton, August 2007). Guedes maintained a long friendship with Archigram’s Peter Cook, eventually attending his ArtNet Rallies in London (telephone conversation with Pedro Guedes, November 2008).

[10] Guedes was also featured in ‘Y aura-t-il une architecture?’, «L’Architecture d’Aujourd’hui», vol. 33, no. 102, pp. 42-49, June-July 1962.

[11] Guedes came into contact with the Smithsons through the South African Theo Crosby, a mentor to Archigram. See Team 10 website http://www.team10online.org/ (accessed 30 August 2007).

[12] They were joined by Jullian de la Fuente. See Team 10 website http://www.team10online.org/ (accessed 30 August 2007).

[13] Gillian Darley, ‘Moses of the Modern Movement’, «Architectural Review», December 2004, http://findarticles.com/p/articles/mi_m3575/is_1294_216/ai_n8686683http://findarticles.com/p/articles/mi_m3575/is_1294_216/ai_n8686683/pg_1 (accessed 30 August 2007).

[14] Pancho Guedes, ‘Introduction’, http://www.guedes.info/contfram.htm (accessed 30 August 2007).

[15] These are cited as sources by Timothy Ostler. For the bearing of the Zimbabwe on African architects in the 1960s, see ‘Introduction’ in Udo Kulterman, ‘New Directions in African Architecture’, New York: George Braziller, 1969.

[16] Guedes corresponded with Oscar Niemeyer (telephone conversation with Pedro Guedes, November 2008).

[17] See Michel Foucault, ‘Of Other Spaces’, «Diacritics» no. 16, Spring 1986, pp. 22-27, based on a lecture given in 1967.

[18] ‘30 Minutes With Pancho: Transcript of conversation with Karen Eicker’, ArchitectAfrica.com, http://architectafrica.com/bin0/news200311112_guedes_interview.html (accessed 30 August 2007).

[19] See Guedes, ‘Vitruvius Moçambicanus’.

[20] See Guedes, ‘A Neo Colonial Revival’, in ‘Vitruvius Moçambicanus’.

[21] See Beinart, op. cit.

[22] See Guedes, ‘A Few Grass Houses’, in ‘Vitruvius Moçambicanus’.

[23] See Cedric Green, ‘Amâncio D’Alpoim (Pancho) Guedes’, ‘Lisboscopio’ (catalogue of the Portuguese representation at the 10th International Architecture Exhibition, 2006 Venice Biennale), available at http://www.guedes.info/contfram.htm (accessed 30 August 2007).

[24] See Hannah le Roux, ‘The networks of tropical architecture’, «The Journal of Architecture», vol. 8 no. 3, 2003, pp. 337-354.

[25] Guedes, ‘Temporary Towers, Slabs and Slices of Street Face’, in ‘Vitruvius Moçambicanus’.

[26] See ‘ex12’, http://www.guedes.info/apcontfram.htm (accessed 30 August 2007).

[27] See G.W.F. Hegel, ‘The Philosophy of History’, 1837, trans. J. Jibree. New York: Colonial Press, 1899, p. 93, 99.

[28] Beinart, op. cit., p. 248.